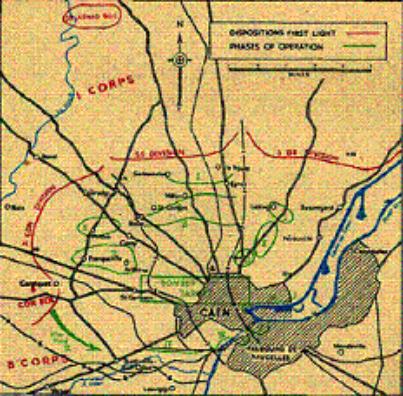

ROBERT WILLIAM2 BRADLEY (ROBERT WILLIAM1) was born

on 28 August 1924 in Edmonton, Alberta and died in battle outside the small

French commune of Cussy during OPERATION CHARNWOOD, the recapture of Caen, Normandy

on 08 July 1944, just one month after the landings. Originally buried within

the limits of the town, his remains were reburied and laid to rest at the

Beny-Sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery in Calvados, France.

The

Landings in Normandy – 6 Jun 1944 (Source C.P. Stacey, The Victory

Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe, Volume III, Official History of

the Canadian Army in the Second World War)

Military

Service:

Military

Service:

Service

Number: M/62082

Age: 19

Force: Army

Regiment: Canadian Scottish Regiment, R.C.I.C.

Unit: 1st Battalion

Additional

Information:

Son

of Robert William and Winifred Gladys Bradley, of Vancouver, British Columbia.

Private

R.W. Bradley is commemorated on

Page

256 of the Second World War Book of Remembrance.

Commonwealth

War Graves Commission

In

recognition of his courage and dedication to his duty, Private Robert William

Bradley was awarded the following War Medals:

Canadian

Volunteer Service Medal (with Clasp)

A

timekeeper for the construction company Bechtel, Price & Callahan in

Edmonton, Robert Bradley enlisted as an orderly in the early months of 1943 as

a member of the 33rd Company, Canadian Dental Corps, following in his

father’s footsteps. By October of that year, Private Bradley had transferred to

the 1st Battalion of the Canadian Scottish Regiment and continued

his training as an Infantry Signaler. Proficient in German and French, he

qualified on 24 March 1944 and embarked for the United Kingdom days later, only

three months prior to the landings at Normandy. Private Robert William Bradley

was killed while fighting alongside the 3rd Canadian Infantry

Division in the fields of France on the 8th of July 1944.

At 0730 hours on the 8th

of July, the second phase of OPERATION CHARNWOOD,

the drive to Caen, commenced. Fresh brigades resumed the advance south, but

soon faced toughening resistance from the interlocking German village

strongpoints. On the eastern flank, the 3rd (British) Division

battled forward to secure the key terrain of Hill 64. In the Allied centre, the

59th Division pressed forward two kilometres (one and a quarter

miles) to capture Saint-Contest, but fierce enemy resistance halted their

advance short of Epron. Further west, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division

battled all day to overcome the fanatical resistance offered by SS ‘Hitler

Youth’ soldiers at Buron. That the spearhead Canadian Infantry Division lost a

staggering 262 casualties that day attests to the ferocity of this encounter.

Nearby, a single Canadian 17-pounder anti-tank gun accounted for no less than

13 enemy tanks. Despite the battle still raging in Buron, the Canadians nevertheless

fought their way forward to capture Authie that afternoon and Cussy by dusk. By

nightfall, therefore, these three concentric divisional thrusts had reached a

line less than one kilometre (950 yards) north of the city.

Click here to view Canadian

Army Newsreel footage on the Battle for Caen.

(Note:

Download time approximately 2-minutes using high-speed Internet)

Burial

Information:

Burial

Information:

Cemetery: BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY

Calvados,

France

Grave

Reference: VI. E. 6.

Location:

Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery is about 1 kilometre east of the village of

Reviers, on the Creully-Tailleville-Ouistreham road (D.35). Reviers is a

village and commune in the Department of the Calvados. It is located 15

kilometres northwest of Caen and 18 kilometres east of Bayeux and 3.5

kilometres south of Courseulles, a village on the sea coast. The village of

Beny-sur-Mer is some 2 kilometres southeast of the cemetery. The bus service

between Caen and Arromanches (via Reviers and Ver-sur-Mer) passes the cemetery.

It

was on the coast just to the north that the 3rd Canadian Division landed on 6th

June 1944; on that day, 335 officers and men of that division were killed in

action or died of wounds. In this cemetery are the graves of Canadians who gave

their lives in the landings in Normandy and in the earlier stages of the

subsequent campaign. Canadians who died during the final stages of the fighting

in Normandy are buried in Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery. There

are a total of 2048 burials in Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery. There is

also one special memorial erected to a soldier of the Canadian Infantry Corps

who is known to have been buried in this cemetery, but the exact site of whose

grave could not be located.

Juno Beach

Mike Red and Green sectors / H-Hour / 7:45 a.m.

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles

German soldiers watched the sea. Hundred

of yards in the distance, landing craft slammed up and down on the

white-crested waves. The Germans swallowed hard and wished the men around them

good luck. There was time to remember what Nazi officers had said. Democracy

made people weak. The Allies were sure to run away when bullets flew. As

fingers tightened on triggers, the German soldiers could only pray that this

was true.

On the water, landing craft came

under artillery fire from shore. The Allied bombardment had sounded so

impressive when the soldiers were miles away at sea. But for all the noise, the

Germans were fresh as daisies in Courseulles. It was once a peaceful harbor

village. Now it was a smoking ruin where only the enemy was alive.

At the back of a landing craft, a

Winnipeg soldier joked to ease the tension. He said, in a funny British accent,

“I say, old chaps, anyone for tennis?” Other men joined in: “Pilot, are you

sure this is the ferry to Paris?” “Home was never like this.” “Not much like

the old ferry back home.” “It’s Paris for me, first chance I get.”

“Can the chatter back there! We’re

going in!”

Enemy bullets beat against the metal

ramps. Then ramps went down and Canadians began to die.

Men fell all around him as Corporal

W.J. Klos thrashed through the deep water. Klos was a big, powerful man whose

nickname was “Bull”. A bullet tore into Corporal Klos’ stomach. A second bullet

tore into his leg. The corporal’s rage was greater than his pain. He staggered

to the beach and shot an enemy gunner. Klos dropped his rifle and fought

another German with his bare hands. Bleeding into the sand, Corporal Klos died

with his hands around the throat of the enemy. Behind him, the Winnipegs

charged through the fire.

Men fell all around him as Corporal

W.J. Klos thrashed through the deep water. Klos was a big, powerful man whose

nickname was “Bull”. A bullet tore into Corporal Klos’ stomach. A second bullet

tore into his leg. The corporal’s rage was greater than his pain. He staggered

to the beach and shot an enemy gunner. Klos dropped his rifle and fought

another German with his bare hands. Bleeding into the sand, Corporal Klos died

with his hands around the throat of the enemy. Behind him, the Winnipegs

charged through the fire.

Captain Phil Gower was everywhere at

once among the men. He organized assaults on the pillboxes and kept the

Winnipegs moving across a fortified bridge. Captain Gower urged men on. He took

off his helmet and waved it in the air to show there was nothing to fear.

Meanwhile, tanks had

landed. Lieutenant “Red” Goff led a troop of Hussar tanks across the bridge and

fired at a camouflaged fort. The Germans shot back and a Hussar tank was hit.

The crew bailed out and all five men were machine gunned and killed. The

Hussars fired on the fort with a vengeance.

Machine gun and mortar

nests surrendered when surrounded by the Winnipegs. A British observer said

that the Canadians went at it like hockey players. But this was definitely not

a game. When the shooting stopped, Captain Gower and twenty-six men of his

company were still standing. More than a hundred Winnipeg soldiers had been

killed or wounded.

The Canadian Scottish

On the right of the Pegs, Charlie

Company of the Canadian Scottish battalion assaulted a fortified chateau at Vaux.

A large German gun had already been knocked out, courtesy of the Royal Navy. A

platoon led by Lieutenant Roger Schjelderup attacked three machine gun nests

and took fifteen prisoners. One of the prisoners led the Can Scots through land

mines, then to an open field beyond.

The soldiers moved

through a field of tall grain in extended formation. The sudden loneliness of

each man was no greater than the pain of homesickness. The fields looked just

like the farms at home. Their German prisoners, held in compounds back on Juno,

would be seeing Canada soon. They would spend the rest of the war on work

farms. One German prisoner of war later described his labor in Canada as

“heaven on earth”.

In Normandy, the Canadian soldiers

pressed on.

Nan Green sector / 7:58 a.m.

The 1st Hussars

Tanks landed ahead of the

Regina Rifle infantry and, firing at close range, took on the German guns.

Peering out his periscope, a soldier

of the 1st Hussars saw another tank “waddle right up to this fort thing. The

tank fired twenty-eight rounds before it was holed. We came alongside him. The

fire was very heavy. Guns were popping off everywhere and machine gun bullets

pelted our hull. We broke through the wire into the dunes and among the

fortified houses. We wheeled around and spotted an anti-tank gun behind the

casement. The Jerries were manning it, but we crashed through a brick wall and

surprised them.” Two direct hits passed through a gun shield and the German gun

blew up.

A tank is a moving metal box with

guns sticking out. On the inside, it’s like a two-storey fort for the five-man

crew. The commander, gunner, and gun loader are on the upper level. Below them,

separated by a metal floor, sat the driver and machine gunner. When the hatches

were closed, the men peered out through periscopes and talked to each other

over a wireless. An enemy shell could “hole” the metal wall of a tank, and the

shell would explode inside. If the crew survived the blast, there was little

time to escape before the fuel and ammunition blew up. A tank could become an

incinerator at any moment in battle.

The Regina Rifles

The Reginas were stopped at the seawall by

enemy fire. Able Company commander Major Duncan Grosch was wounded.

Lieutenant Bill Grayson had a daredevil spirit.

And he didn’t want to let his commanding officer down. Lieutenant Grayson ran

through a gap in the barbed wire and made it to the side of a house. A concrete

gun emplacement, blasting the beach, was down an alley. Between Grayson and the

emplacement was more barbed wire and a machine gun nest. The machine gun fired

on a fixed arc at regular intervals. Grayson calculated there was just enough

time between bursts of fire to reach the emplacement.

The lieutenant made a mad dash but got

entangled in the barbed wire. Perhaps the German gunner was surprised because

the machine gun stopped shooting. It was just for a few moments but that was

long enough for Grayson to tear himself free. He tossed a grenade through an

aperture in the emplacement. The grenade exploded and the lieutenant dived in.

He got to his feet in time to see the gun crew race out the back door. The last

man threw a grenade. It landed between Grayson’s feet. The lieutenant picked it

up and threw it back at the German. The enemy soldier escaped before it went

off.

Lieutenant Grayson raced after the enemy

through the back door and into a trench. It zig-zagged to an underground

shelter. Down the hole, Grayson could see the enemy, and heard shouts of

"Kamerad!". Grayson motioned with his pistol for the Germans to come

out. Trapped by one incredibly brave soldier, thirty-five Germans surrendered

and their artillery gun was destroyed.

About 8:10 a.m. / Nan White sector

The Queen’s Own Rifles

Rifleman Doug Hester and Rifleman Doug Reed

were singing "For Me and My Gal" as they watched the shore. Then

ramps went down in crossfire and Doug Reed was dead. Three other men were

killed in the first seconds of their war. One was Fred Harris, the son of a

Toronto doctor, who had turned down every chance to be somewhere else on D-Day.

Hester jumped from the craft. The riflemen,

drenched and freezing, splashed their way to the obstacles for protection. A

burst of gunfire went through Corporal John Gibson’s back pack. Corporal Gibson

turned to Hester, grinned, and said, “That was close, Dougie." Then

another burst of gunfire killed him.

The beach ahead was 200 yards of open ground

that ended at a ten-foot high seawall. The whole area was swept by enemy fire.

Major Elliot Dalton led men to the wall. Two thirds of a platoon fell to the

sand. Sergeant Charlie Smith was wounded but fought his way with ten survivors

to the Bernières railway station. Glass shattered and wood splintered as they

were hit with gunfire from houses along the street. Sergeant Smith collapsed

and a corporal took over. Five men of the platoon were still able to fight.

Using a Piat, the Canadians blew a hole through the wall of a house, and the

explosion killed the German snipers inside.

Riflemen “Boots” Bettridge, Bert Shepherd, and

Sergeant Major Charlie Martin ran to the wire beyond the railway tracks. Martin

ordered Rifleman Shepherd to use the wire cutters. Shepherd said, “Cut it

yourself, you’re paid more.” Martin cut the wire.

8:30 a.m.

Le Régiment de la

Chaudière

Behind the Queen’s Own Rifles, tanks of the Fort

Garry Horse were landing. And behind the tanks was the infantry battalion from

Quebec: Le Régiment de

la Chaudière.

The tide was quickly rising, and mined

obstacles were underwater. Five of the Chaud’s landing craft hit mines and sank.

Soldiers struggled to reach shore, losing equipment and weapons in the surf. A

navy captain reported that one group of infantry “still had their knives and

were quite willing to fight with this weapon alone.” The French Canadians (most

did have rifles) advanced into Bernières where the residents were thrilled with

their liberators. The regiment’s diarist wrote, “Les francais sont assez

accueillants et beaucoup nous acclament au milieu des ruines de leurs maisons.”

(“The French, surrounded by the ruins of their houses, welcomed them with open

arms.”)

Bernières was ringed with German artillery. The

Chauds and a machine gun platoon of Cameron Highlanders were pinned down at the

main exit from the village.

Lieutenant Walter Moisan led an attack. A smoke

grenade he carried stopped a bullet. This might have been lucky, but the

grenade ignited and set fire to Moisan’s uniform. Still, he stayed at the head

of the attack until the enemy position was overrun.

Nearby, a German gun hit the Queen’s Own Rifles

as they gathered beside a church. Captain Ben Dunkelman set mortar weapons in a

ditch about two hundred yards from the German artillery. Corporal Tom McKenzie

saw the mortars fire. There was a blast and Dunkelman jumped in the air with

his hands over his head in victory.

By 11:40 a.m., another brigade was landing. So

many soldiers in one place were a perfect target for the big German guns, but

men such as Captain Dunkelman and Lieutenant Moisan had cleared the way

forward. The one man was a Jewish Canadian; the other was French Canadian. The

soldiers behind them were Scottish Canadians. United as a country, diversity

was strength.

The Maple Leaf flies over Juno beach today.

Click here for a Map of the Juno Landings Click here for a Picture of the Juno

Monument